In today’s lesson, we started by showing you the artefact below, and asked you what you thought it was.

Some of you noted that it contained glass tubes, and wondered if it was connected to taking blood pressure. A couple of you got it right – it is in fact a portable blood transfusion kit dating to around the 1900s, and is on display (usually) in our History of Medicine collection in the Brighouse building.

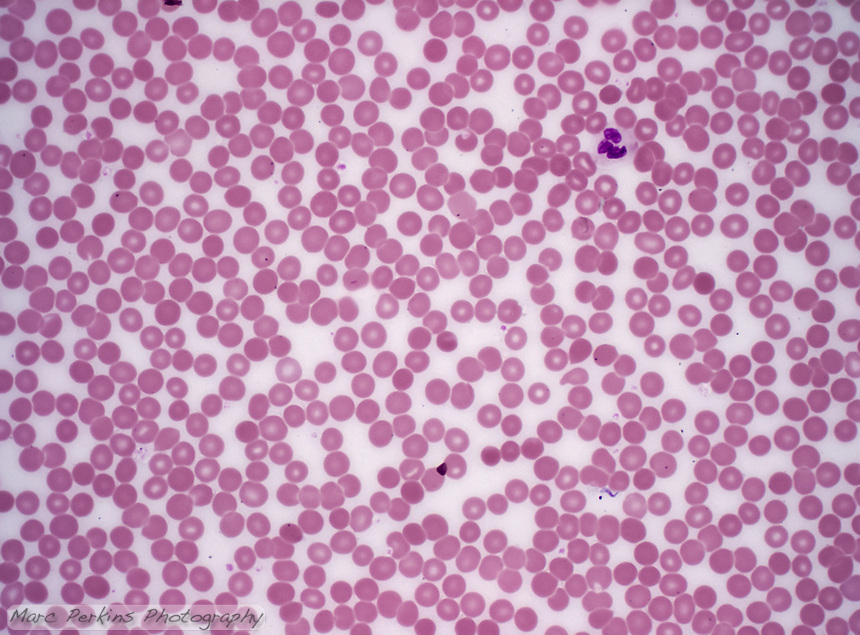

We showed you an image of blood under a microscope, followed by an image of the sorts of things you find in blood: red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets (for clotting). We then played you a short video which outlined how a surgeon in the 1800s successfully transferred blood from a living person into a hemorrhaging woman who had just given birth. We asked you what might be the problem with this sort of procedure. A number of you pointed out that if blood groups weren’t compatible, then the person would have a fatal reaction.

We asked you to make a note of the main blood groups – most of you got some of them and a small number of you got all the AB and rhesus blood groups correct. Certain antigens can be found on the surface of our red blood cells, and these antigens are what defines our blood group. If you are in the A – blood group (like me), then this means your red blood has red antigens on its surface, but no rhesus antigens (which is why it is called “negative”). If I were to be given A + blood, this would be a problem, as my blood would create antibodies against the rhesus antigens in the A+ blood. O+ is the most common type of blood group in Britain, but we showed you a number of charts which demonstrated how blood group statistics vary according to different groups of people.

We had handed out envelopes at the start of each lesson, and in these, we assigned each of you a blood group. We asked you initially to work out which blood groups of the people sitting near you would be compatible with yours, and then we asked you to fill out a graph to work out which blood groups could be received by which, and vice versa. The competed graph showed that O- is a “universal donor”, meaning it can be received by anyone, since it contains no antigens on the surface of its red blood cells. However, AB+ is a “universal recipient”, since it can receive any type of blood, seeing as it already possesses all the antigens. Mr Gimson discovered during the lesson, by using a simple home test blood group kit, that he is O-, and hence, is a universal donor.

We played you a recording by Dr Emily Mayhew, about the importance of the portable blood transfusion kit in wartime, and how scientific knowledge developed so that blood groups were discovered, and storage of blood was improved, leading to great advances in lifesaving treatment, both during the wars, and in peacetime.

We finished by looking briefly at the evacuation of casualties, including the importance of X-rays and the Thomas Splint. We will return to this next Friday.